The natural habitat of wild animals without any regard or plan for how they will cope up with it

Though there was palpable fear among the residents of Sainik Farms when a leopard happened to stray into the colony on December 2, 2023, Vidya Athreya, a senior scientist at Wildlife Conservation Society – India, who has been working on human leopard interaction since 2003 when she started researching the ecology of leopards in human use landscapes in India, in an article quoted social geographer Frédéric Landy of the University of Paris as saying in the context of one such episode: “It wasn’t the slum dwellers—the people most often attacked—who were calling for leopards to be removed. It was politically empowered upper-class residents of high-rises near the reserve who relished the green view but panicked if a leopard so much as showed up on a security camera”.

Excerpts from the article: In 2011 Sanjay Gandhi National Park got a new director, Sunil Limaye, who faced a serious problem: a history of leopard attacks in and around the reserve. At their peak, in June 2004, the cats attacked 12 people, most of them living in slums at the inner edge of the reserve forest.

Limaye was familiar with my work in Junnar, and he had an idea about what the problem was. For years the forest department had been releasing leopards trapped around SGNP and elsewhere into the national park in relatively large numbers—15 in 2003.

But relocation didn’t help: another leopard swiftly took over the vacated territory, and attacks near the release site were likely to increase. Although a lot of forest officers understood this dynamic, the pressure from politicians and the media to remove leopards was immense.

Limaye wanted to start an initiative involving scientists and the citizens and institutions of Mumbai to reduce the leopard conflict, and he wanted me involved. I was busy writing a Ph.D. thesis on the work I had done in Akole, but I couldn’t resist the chance to help resolve a terrible situation for leopards and people alike. Plus, my sister had moved to Mumbai around that time, so my daughter could play with her cousin while I worked.

Limaye put together a team that included me, several forest officers and Vidya Venkatesh, director of the Last Wilderness Foundation.

Many of Mumbai’s residents regarded the forest as a source of trouble, and our group agreed that mindsets had to change. The surest way to make that happen was to get Mumbaikars involved.

We recruited wildlife enthusiasts who’d long wanted to help protect a nature preserve they loved. They formed an association, Mumbaikars for SGNP, and began a campaign to educate their fellow citizens about the value of the national park as a reservoir of green space and a source of water and oxygen. Local students set up camera traps to count leopards.

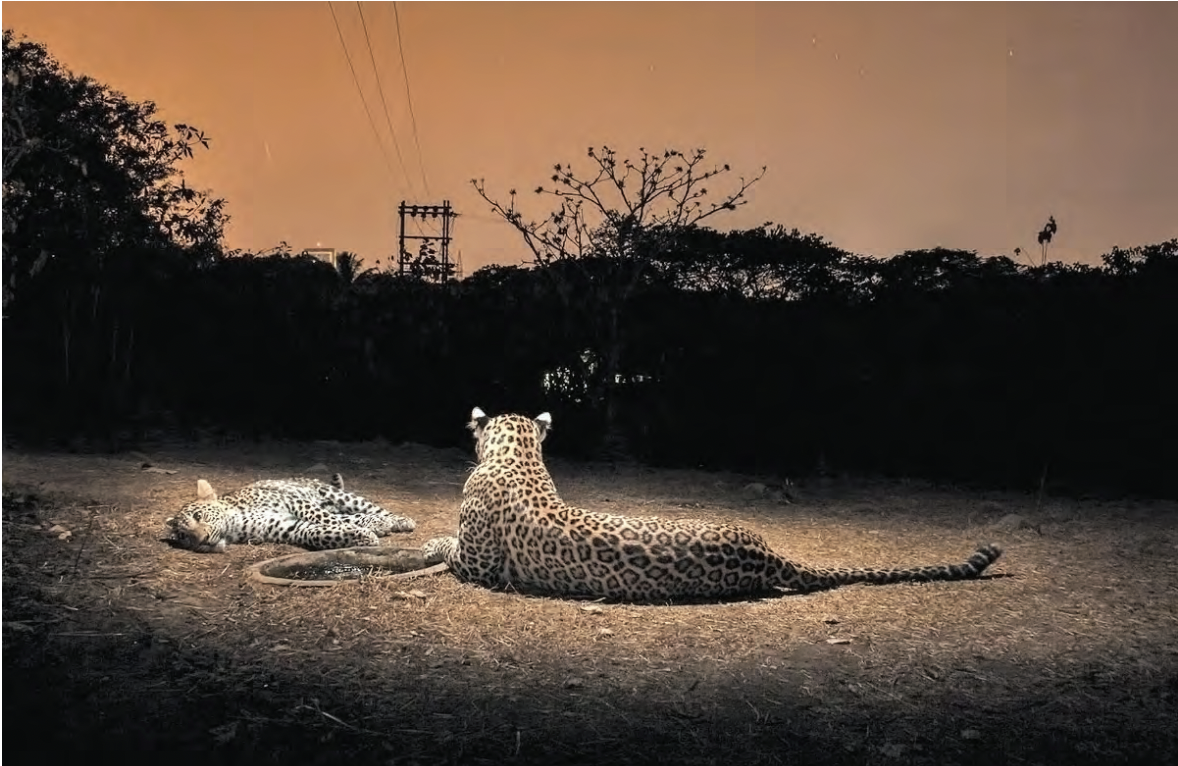

In 117 square kilometers in SGNP and the Aarey Milk Colony, a nearby scrub forest given over to cattle for milk production, the cameras captured 21 leopards—a very high density.

The national park had wild prey, mainly deer, but the leopards were clearly being attracted to the slums by the many feral dogs that were feeding on the garbage strewn around.

We also interviewed people to understand their interactions with leopards. As social geographer Frédéric Landy of the University of Paris has noted in his work, it wasn’t the slum dwellers—the people most often attacked—who were calling for leopards to be removed. It was politically empowered upper-class residents of high-rises near the reserve who relished the green view but panicked if a leopard so much as showed up on a security camera.

Interestingly, the Warlis and Kohlis, Indigenous peoples who worshipped Waghoba and who had lived in the forest for centuries before Mumbai expanded to surround it, were not afraid of leopards and rarely experienced attacks. They wanted the carnivores there to scare off encroachers and developers. As the research and the awareness-raising program proceeded, the forest department improved its ability to handle leopard-related emergencies—one being cornered in the urban area, for example. The department also worked with the police to increase their capacity to control mobs that might seek to attack these animals and, perhaps most important, with the municipality to initiate garbage collection in areas around the park frequented by leopards.

Once our report came out, we worked with the Mumbai Press Club and other media organizations to advise people about how they could stay safe: keep their surroundings clean, don’t let children play outdoors after dark, illuminate unlit environs and move away from a leopard if they spot one. As humans, we believe that only we have agency. But like tens of millions of people in rural India whose forests and fields are being converted to mines, factories, dams and highways, animals must adapt if they are to survive in an increasingly challenging world.

The biology of large cats dictates that they roam across tens or hundreds of kilometers to find mates and have cubs; failing such dispersal, inbreeding and, with it, extinction are imminent. It is because these felines refuse to be confined to the 5 % of India’s land surface designated as protected that—alongside 1.4 billion people—the country continues to shelter 23 % of the planet’s carnivore species, including at least half the world’s tigers, the only surviving population of Asiatic lions and almost 13,000 leopards. But they must not cause so much harm that people retaliate. Around the world the primary threat to big cats is humans.